7:00

News Story

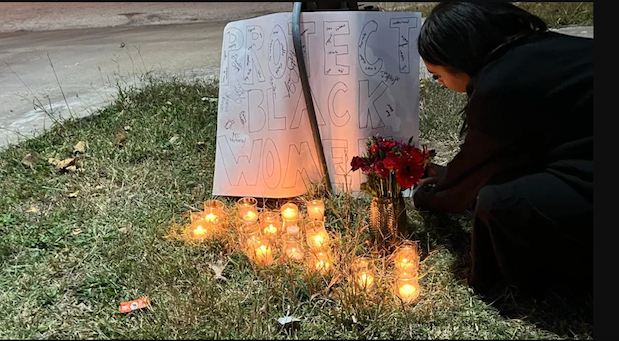

Spotlight is on Kansas City and its problem of missing black women

Kansas City police insisted that rumors of a serial killer targeting Black women were false. Now that a kidnapped Black woman has been found, the story is not as cut-and-dried

This story was originally published by the Kansas City Beacon.

On Oct. 7, a terrified 22-year-old Black woman escaped from a home in Excelsior Springs. She told police she had been locked up there for about a month, after being abducted from Prospect Avenue in Kansas City by a man who lives in the home.

The man, Timothy M. Haslett Jr., 39, is in custody facing charges of rape, kidnapping and assault in Clay County. The woman told neighbors and police that she was restrained in a small room in Haslett’s basement, where he repeatedly raped, beat and tortured her. She managed to escape when he took his elementary-age son to school.

The woman told a neighbor and police something else: There were other victims, she said. Women who “didn’t make it out.”

The woman’s escape and Haslett’s arrest occurred a month after The Kansas City Defender, a Black-owned news publication, republished a video of Bishop Tony Caldwell, a community and church leader, alerting the public of assertions that at least several Black girls and women are missing from the Prospect Avenue corridor.

“We got four young ladies that have been murdered within the last week off of here at 85th and Prospect,” Caldwell said in the video. “We got a serial killer again.”

After the video went viral on social media, the Kansas City Police Department released a statement calling Caldwell’s assertions “completely unfounded.” The department makes the public aware of every homicide it investigates, the statement said. It said police had responded to one homicide of a woman in six weeks, at a location not close to Prospect Avenue. Several local news outlets, which had not reported on Caldwell’s allegations, did report the police rebuttal.

Authorities in Kansas City and Excelsior Springs have told news outlets they have not found a link connecting the woman imprisoned in Haslett’s home with any other reported missing or murdered women. A police investigative squad in Clay County is working the case and searching for any other victims.

But the woman’s emergence, and her story of being abducted in Kansas City, has roiled Black leaders and residents. They contend that the events are proof that police don’t take reports of missing Black women seriously and that mainstream news outlets are too quick to accept the police version of events.

“I’m tired of hearing these excuses. I’m tired of hearing people thinking what people know, instead of going to the people and seeing who they are,” said Gloria Ellington, the founder of GYRL, a nonprofit she started in 2000 with the mission of empowering women, especially victims and survivors of domestic violence. Ellington is part of the group searching for missing women and girls along the Prospect corridor.

What’s happening?

Caldwell said he began to fear for the welfare of multiple Black women in Kansas City after he helped a father search for a 15-year-old girl who went missing from the area in mid-September. The teenager was eventually found. But in the process of looking for her, Caldwell and other canvassers ran across information about other missing girls and women.

“All this information started coming out, as we were looking for a totally different person,” he said.

Local activists say it isn’t uncommon for young women to go missing from the area generally known as the Prospect corridor, which frequently records some of the city’s highest crime rates.

Two years ago, Caldwell and others conducted a search for 38 individuals they had been told were missing.

“Out of that, 32 of them happened to be African American. And we were able to find 13 of them,” he said.

Nationally, of 300,000 missing girls and women reported in the U.S. in 2020, a third of them were Black, according to PBS NewsHour. In Kansas City, the proportion is the same.

Black Kansas Citians are acutely aware that concerns about missing women too often prove to be correct. In 2004, 47-year-old Terry A. Blair was charged with murdering six women near Prospect Avenue. He was convicted in 2008.

Barriers to filing missing persons report

The recent confluence of events has also raised questions about whether Kansas City’s requirements for initiating a missing person investigation are too stringent.

According to KCPD procedure, an adult missing person report will be completed when a preliminary investigation determines that the person was last seen in Kansas City and meets an additional requirement, such as being under professional care for mental health issues, or under threat from domestic violence or another reason.

While the requirements for reporting missing juveniles are different, parents still confront issues in trying to complete the reports.

“We had a lady there today that talked to us. She tried to file a report with her daughter, it didn’t happen,” Caldwell said. “They told her, ‘We don’t even know if you have a daughter or not,’” he said.

The father of the 15-year-old girl whom Caldwell helped search for in September came to him because of roadblocks he confronted in trying to report her missing to the police department, Caldwell said.

“He found us out because our name was already out there of us doing certain things like this in the community, working with people that nobody else will work with,” Caldwell said.

A long history of mistrust has also left members of the Black community with a reluctance to disclose information to the police.

“We all know that a lot of people in the streets do not trust the police. So they don’t talk to the police about certain things,” Caldwell said.

“With things going on and on about police brutality, a lot of people, if they have information, they’re still not telling the police, because of distrust and the walls that have been built up. But they’ll talk to us all day long, the community leaders,” he said.

Disconnect between local media and community

Residents of Kansas City’s Black community are also calling out local news outlets, saying they help to perpetuate the silencing of Black Kansas Citians.

“We know that we’ve been incarcerated at a higher rate, so we know that most of us will be disfigured in our commentary to the media. So we don’t talk to them,” Ellington said.

Ellington said she regards the willingness of news outlets to rely on the police response as the only and last word as typical of the media’s disregard of her community. Many Black Kansas Citians depend on social media to get the word out, she said.

“We’ve never had that backing, and we never relied on the media to be our friends. So the word of mouth is the strongest information you can get out there,” she said.

“To talk to each other gets the word out whether somebody comes with a camera or to write. But we’re at the point now that we’re sick and tired of it. And we’re not asking for their permission any longer.”

What’s next?

The kidnapping story and the allegations that concerns about missing women were not taken seriously have drawn reporters from national news outlets to Kansas City. And as interest shows no signs of subsiding, advocates say they are receiving more reports of missing women in the area.

Caldwell called for police in Kansas City to do a better job of hearing and working with Black residents.

“Instead of trying to alienate people, they need to learn to embrace people,” he said. “How they word things means a lot. This community is already hurting. Don’t traumatize us any more.”

Black leaders are also asking for a less onerous process for reporting a person missing.

“I don’t care anymore about them saying if it was a report or not, we still have people missing,” Caldwell said. “Our thing is, let’s bring them home safely. Let’s not try to prove a point.”

Change can happen on a personal and communal level, Ellington said.

“We need to get back to what we were created to do, and that is to be a servant of each other,” she said. “To help the voices rise that can’t speak for themselves.”

The Kansas City Beacon is an online news outlet focused on local, in-depth journalism in the public interest.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.