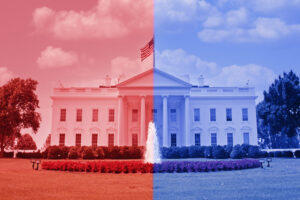

Flush with ambition and cash, a newcomer arrives like a bolt from the blue. Or, in Missouri’s case, red.

He jumps a line of aspirational politicians, lands in a statewide elected office and immediately sets his sights on a higher target, heedless of the wreck just up the road.

Missouri has seen this movie twice in four years.

The original performance starred Eric Greitens, who was largely unknown before he began his improbable but successful 2016 run for governor, only to be forced out of office after two years, enveloped in scandal.

The sequel features Josh Hawley. His first elected office, also gained in 2016, was state attorney general — a job that traditionally has gone to politicians who have spent years in the trenches of the state legislature. Two years later, Hawley vaulted to the U.S. Senate. He is now facing nationwide wrath for prolonging baseless doubts about Democrat Joe Biden’s election, and for encouraging insurrectionists with a fist pump before they stormed the U.S. Capitol.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Outside of President Trump’s deep red base — whose votes and affections Greitens and Hawley both covet — the actions of the two wunderkinds have left many Missourians embarrassed and wondering how their state has become the cradle for ambition gone so wildly awry.

The explanation begins with the two men themselves, who both grew up in Missouri, went elsewhere and returned with the intention of using the state as a launching pad for their presidential ambitions.

Greitens settled in the St. Louis area and founded a non-profit to help military veterans. Hawley landed a job as assistant professor at the University of Missouri School of Law in Columbia.

While Hawley was conscientious about teaching his classes and meeting with students, he showed no interest in the life of the university or the usual faculty activities, said Frank Bowman, a professor at the law school.

“It became clear that personal advancement was the priority behind which everything else had to fall,” said Bowman.

The author of a recent book, High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump, Bowman has been sharply critical recently of both Trump and Hawley. He contributed about $500 to Democrat Claire McCaskill, Hawley’s opponent in the 2018 U.S. Senate race.

In their 2016 campaigns for office, Greitens, 42 at the time, and Hawley, 36, tapped into a populist preference for newcomers — as well as enthusiasm for Trump, who won Missouri by almost 19 points.

“I think Republicans are inclined to vote for folks who are making their initial run,” said John Hancock, a political consultant and former Missouri Republican Party chairman. “There is some dissatisfaction with the institutional Republican figures and that has manifested itself in allowing new and fresh faces to vault their way to the top.”

Both parties are seeking candidates with selling points, like military service, that don’t include a trail of votes, Hancock said.

“When I started in this business, we would give slogans to our candidates,” he said. “It’s probably been 10 years since I’ve used the ‘experience counts’ slogan.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

The aspiring newcomers benefited from Missouri’s wide-open campaign financing laws.

“Both of these guys had access to a tremendous amount of money early,” said Terry Smith, a professor of political science at Columbia College. “That was certainly important for Greitens and allowed him to almost come out of nowhere.”

Candidates could receive unlimited contributions to their personal campaign committees in 2016. Greitens, who defeated several primary opponents and Democratic state Attorney General Chris Koster, raised more than $30 million, including a $13 million contribution from the Republican Governors Association. Voters have since limited contributions to candidates’ campaign committees to $2,600, but donors can still channel unlimited amounts through political action committees.

In both his statewide runs, Hawley benefitted from the sponsorship of former U.S. Sen. John Danforth and mega donors in Missouri, like Joplin businessman David Humphreys.

“He was the anointed one,” Smith said. “He was fast tracked. When you get the endorsement of somebody like John Danforth and when you get the money of somebody like David Humphreys, that’s going to really help.”

When seeking office, Hawley and Greitens sidestepped the state’s traditional party apparatus. Instead of building relationships with Missouri politicians and groups, they worked with out-of-state consultants and relied on expensive media buys to introduce themselves to voters.

Greitens touted his service as a U.S. Navy Seal. Hawley used his legal resume, which includes clerking for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts.

The absence of party vetting, as Missourians have learned, comes with risks.

“Once upon a time, both of the political parties basically said, ‘wait your turn,’ and enforced that,” Smith said. “You had your occasional embarrassments, but nothing like what we have now.”

Once in office, Greitens and Hawley continued to rely on out-of-state operatives to build their political brands, raising concerns among ethics watchers that they were mingling state resources with political activities.

Greitens’ closest advisers hailed from Georgia. Hawley stuck with OnMessage Inc., a national strategy firm known for keeping a tight grip on its clients’ image and activities. News outlets eventually got ahold of private emails showing political operatives from OnMessage coordinating with taxpayer-paid staff in the attorney general’s office. Among other things, they scripted a 2017 raid on massage parlors in Springfield designed to portray Hawley as the fearless protector of human trafficking victims.

Both neophyte politicians shunned legislators and leaders in their own party and were quick to pick fights on social media with mainstream news reporters and outlets, interest groups and anyone inclined to question what they were doing.

With Hawley, that combativeness has increased with his ascension to the U.S. Senate. His Twitter feed shows him lashing out at certain Missouri newspapers (“rags”) “big tech,” “corporatists,” the “new left,” China, and anything he considers “woke.”

“I have been surprised by the kind of vituperative quality of many of the things Josh has said,” Bowman said.

Greitens was notoriously nasty in person and on social media during his abbreviated stint as governor. Few people in Missouri today care to revisit his pugilistic nature or the abusive extramarital affair and brazen, ongoing corruption that eventually did him in. His initial steps last year to form a political action committee for a future run for office sent shudders throughout the state. Taking a page from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels, he is Missouri’s Voldemort — He Who Shall Not Be Named.

Hawley’s legacy remains to be written. National pundits believe he has “immolated” his presidential prospects with the fist pump and his willingness to defy U.S. Senate leadership and turn the Electoral College certification process into a brawl. But many Republicans at home are sticking with him, and there is no sign at the moment of a Democrat with the drive and resources to challenge him for his Senate seat in 2024.

But this is Missouri, home of unbridled ambition and unlimited cash. Anything could happen.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Barbara Shelly