Kansas City’s downtown took on a campus-like feel in early February as 8,000 visitors congregated at the downtown convention center and fanned out to nearby bars, coffee shops and tourist sites.

The guests included students, immigrants, people of color and people who identified as LGBTQ, in town for the annual conference of the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP).

The conference went off smoothly, and most attendees left Kansas City happily unaware of the angst that preceded the event.

Last April, as the Missouri legislature was in session, the AWP published an open letter, saying its leadership was “appalled and deeply concerned” about bills that would threaten health care and quality of life for transgender people.

“We share in the concern for the safety of LGBTQIA+ attendees and allies while attending #AWP24 in a state where these bills are under discussion,” the letter said, using the hashtag for the conference.

The association had booked the convention center in 2015, and the event was rescheduled from 2021 because of the COVID pandemic, leaders explained.

“It is financially and legally impossible for us to cancel, move or postpone the conference out of Kansas City,” the letter said.

But just knowing such a possibility was considered is another reason to wish, however futilely, that cities could operate independently from the states in which they reside.

Kansas City is an aspiring region, seeking to capitalize on its sports teams, new airport and overall good vibes, and to present itself as a welcoming city for visitors, companies and new residents.

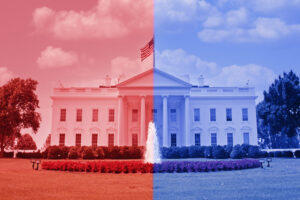

The Republican-run Missouri legislature wants to push the limits on gun access, deny that gender identity can be fluid, ban abortions and crack down on anything that might be considered “woke.”

The city and state are in conflict and, given Republican supermajorities in Jefferson City, the state has the upper hand.

But Missouri’s Republican priorities are harmful for Kansas City. That became glaringly apparent on Feb. 14, when terrified adults and children scattered after gunfire broke out as thousands of people were celebrating back-to-back Super Bowl wins for the Chiefs football team.

A valued member of Kansas City’s community, Lisa Lopez-Galvan, was killed. More than 20 others were taken to hospitals. People were traumatized.

As details about the shooting came to light, so did revelations of Kansas City’s sky-high murder rate — 180 deaths in 2023.

The people charged so far in the Feb. 14 shooting are locals, young men in their teens and early 20s. They showed up at a crowded event with weapons stuffed into pockets and backpacks, prosecutors say, and the shooting reportedly started because of a vague suspicion among some of the accused that others were looking at them the wrong way.

It was the most common type of Kansas City homicide: born of a petty dispute and enabled because guns are rampant.

Republican Gov. Mike Parson, who was at the celebration at Union Station, blamed “a bunch of criminals, thugs out there.” But the correlation between Missouri’s loose gun laws and rising homicide rates in the state is well established, and the legislature has passed laws making it difficult for cities, and even the federal government, to reduce the number of weapons in circulation.

With lawmakers unwilling to budge, Kansas City must attempt to reduce homicides with different policing strategies and a renewed push for conflict resolution and violence prevention measures.

On other matters, city leaders and boosters spend a lot of time trying to reassure outsiders that Kansas City does not share the values of the Missouri legislature or statewide officeholders.

In the weeks leading up to the AWP conference, the writers’ association emailed a list of resources for LBGTQ visitors and allies. People on the list received welcoming letters from state Sen. Greg Razer, who represents parts of Kansas City, and Joel Barrett, vice president of the Mid-America LGBT Chamber of Commerce, who was the city’s official ambassador for the event.

“I know many of you have been apprehensive about coming to our state, and I understand that,” Razer wrote in his letter. “Missouri is a tough place at times — and this is one of those times. Laws being passed by my colleagues are detrimental to our state and our people.”

Razer assured the expected visitors that Kansas Citians would welcome them, just as they had welcomed him, a gay man, when he moved to Kansas City in 2001.

Someday, Razer promised, “Missourians will right these wrongs, and we will once again become a deep-purple state, frustrating both the far right and left with our moderate leanings.”

We can hope.

In the meantime, Missouri’s cities must rely on damage control, workarounds and apologies for the actions of a state legislature and administration that doesn’t care about their aspirations or even the safety of their people.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Barbara Shelly