5:45

Commentary

If you do not know your history or, worse still, know it but deny it, how on earth do you expect to learn from it and move forward?

Unfortunately, many leaders in government who can take actions or propose measures to correct persistent issues are either denying, ignoring or redefining history to disavow whether there is anything wrong or needs fixing.

Examples of such disavowal abound in legislative bodies across America with far-reaching consequences in shaping attitudes and beliefs. This impedes the passage of necessary public policies in many areas — too many to cover in this space.

However, there are two areas, in Missouri and nationally, where the vestiges of history continue to heave the sickness and ugliness that won’t stay down and beg honest assessment and corrective measures.

1) the treatment of vulnerable children; and

2) persistent racial inequality

At the national level, there has been the revelation of what was a pervasive practice of abusing Native American children to the point of death. For over a century, hundreds of thousands of these children were shuttled off to boarding schools across many states between 1869 and 1970 in efforts to indoctrinate them into becoming more American-like.

Unmarked mass graves with hundreds of victims are being discovered.

The U.S. Department of Interior has committed to fully examine the intergenerational impact of this atrocious period in America’s history.

But, after the findings, what will be done about it?

In Missouri, a state House committee has spent the last year investigating the state’s response to allegations of abuse at religious boarding schools that have operated for decades without any state oversight.

A NBC News investigation found that in at least 23 states, including Missouri, these schools are not even required to report they exist. Another 17 states, including Missouri, exempt religious boarding schools from licensing and oversight by state child welfare and educational agencies.

After hearing testimony from those who had suffered abuse, Missouri passed a new law requiring licensing and stricter oversight of boarding schools.

Unsettling questions remain: Were patterns and practices of abuse, before the recent revelation, ignored or totally denied for decades? Is it prevalent at other boarding schools?

But boarding schools are not the only issue.

Just last week, two other areas that the Missouri legislature needs to address have come to light. A Federal watchdog report finds that Missouri fails to report and protect missing foster children. Another national study reveals that children in Missouri have elevated levels of lead in their blood that is higher than that found in children in almost any other state. How long have these children suffered?

A deeper look at the state of the education of vulnerable children overall reveals that there continues to be a lack of understanding, denial or the tendency to ignore the gross disparities that have existed and continue to exist in public education systems across America.

Systemic disparities not only exist between Blacks and whites, but also between the disadvantaged poor and other socioeconomic classes when you examine the history of how America has educated its children.

These disparities in education have existed since the founding of our nation and they have impacted the quality of life for Native Americans and Blacks most predominantly.

But perhaps no area is more subjected to a lack of historical understanding, distortion, or total denial than race and race relations. Most recently this has been seen by all the growing animus and objection to teaching “Critical Race Theory” in secondary schools, colleges and the military.

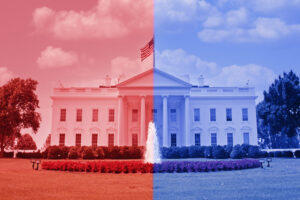

Whether the meaning and purpose of critical race theory is fully understood or not, the issue has become divisive and politicized. More than 27 states with Republican legislatures have introduced bills that would prevent critical race theory from being taught in schools. A bill has even been introduced in the U.S. Congress.

The Missouri legislature has also held hearings on whether to ban the teaching of critical race theory when there is no apparent evidence that it is currently being taught.

While there may be much to dread and regret, there is much more to gain in facing history at the state and national level when it comes to race. Not to do so continues to be a major impediment in eliminating systemic racism and inequality.

Then why not be committed to knowing all the history of Missouri or whatever state you call home, of America, and embrace it being included in the curricula being taught in our secondary schools and higher institutions of learning?

Fortunately, thousands of teachers in more than 115 cities across the nation are coming together to stand for what they label as “teaching the truth.”

The U. S. Conference of Mayors during its annual meeting this September adopted a resolution in support of teaching critical race theory in K-12.

Looking at the well-being of the vulnerable children among us and pervasive racial inequality are just two areas where history is often ignored or denied.

To not fully understand and acknowledge all of history — the good, the great, the bad, the despicable — is to forever operate in a false reality, fooling ourselves to our detriment and thwarting the kind of state or nation we could become.

Such denial and fear of history is grossly misplaced.

While egregious acts committed by our ancestors cannot be undone, we need not be a part of them continuing. As Missourians and Americans, we can neither absolve, totally insulate ourselves, nor live a life of detachment. State and national leaders certainly cannot and should not.

So, why not acknowledge that dreadful things indeed happened in our state and in our nation and try to fix them? If not fix them, commit to charting a different path to stop the vestiges of those actions that still linger and cause grave harm today.

That is what knowing, acknowledging and understanding all the history of Missouri, or your state, and of America will do.

Or should do.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Janice Ellis