8:21

News Story

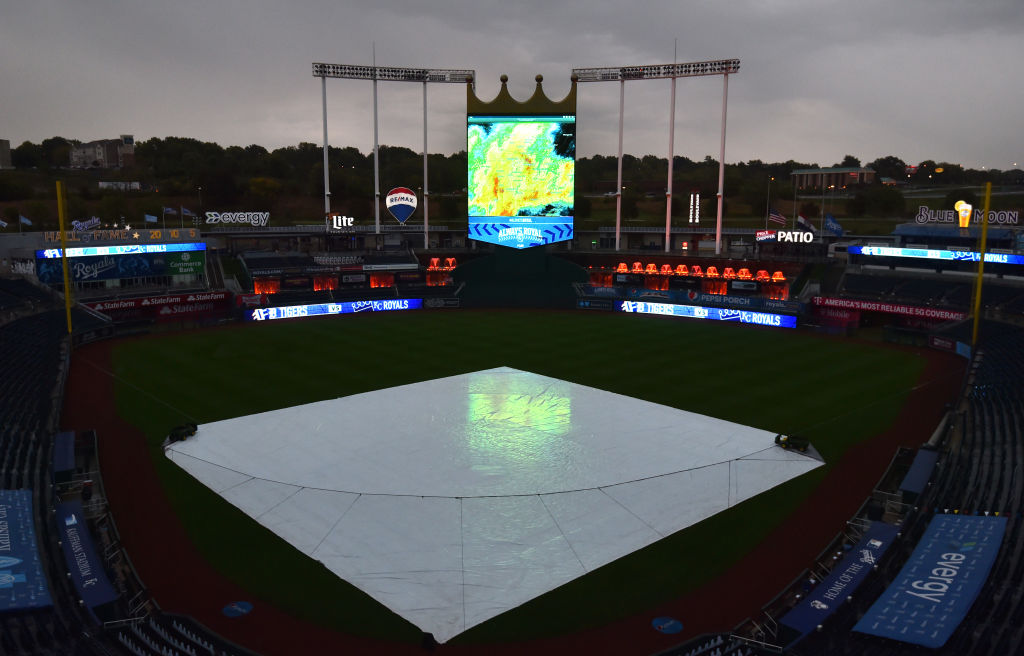

Kansas City service workers push for protections as Royals look to build downtown stadium

Workers are left with unanswered questions about community benefits as Royals push to build a new $2 billion downtown stadium and entertainment district

This story was originally published by the Kansas City Beacon.

Bill Thompson cooks at a fast-food restaurant, shares a car with his wife and helps care for an older family member. He’s got a lot to manage, but Thompson has found time to attend “listening sessions” that the Kansas City Royals have organized to discuss plans for a new downtown ballpark.

“We want to have a seat at the table,” Thompson said.

He’s talking about Stand Up KC, a coalition of fast-food, retail and other low-wage workers around Kansas City who advocate for better pay and conditions. The group has organized unions and supported job actions at fast-food restaurants. Now it is focusing its energies on the $2 billion stadium and accompanying entertainment district that the Royals want to build.

The team announced last year that it is planning to leave Kauffman Stadium after 50 years. The team’s lease is good through 2031, but the Royals are looking to move sooner, probably to a site in or near downtown Kansas City.

Team officials have hosted three sessions to talk about the merits of a new stadium and ballpark district, and to gather community input. Members of Stand Up KC have been present at all three. Organizers want to ensure protections for hourly workers in the form of a community benefits agreement.

Thompson has been a cook at Burger King for 10 years, making $12 an hour. He has one car, which he drives to work, but he often has to walk home so his wife, a visiting nurse who makes the same hourly wage as he does, can use the car. The couple cares for Thompson’s mother-in-law, who helps them afford their home with her disability check.

“If something happened to her, with our wages, we wouldn’t be able to keep our home,” Thompson said.

The way he sees it, the ballpark, which is being proposed as “an uplifting and beneficial project,” should agree to decent wages and benefits for future workers.

“We want labor with dignity and respect for the workers. I can’t retire. I can’t afford to go to a doctor. These are the things that these workers don’t need to suffer through,” Thompson said.

New downtown Royals stadium

According to the Royals, the opening of the $2 billion ballpark and entertainment district would create 2,200 jobs, mostly in the service and retail sectors. Those jobs would spur $200 million in annual labor income and $500 million in annual economic output, according to the team.

But for Kansas City workers, this isn’t enough.

“What kinds of jobs are they going to be? Are they going to be more poverty wage jobs where we’re still seeking public assistance because our wages aren’t enough to meet our needs to put food on the table?” Thompson said.

In its community benefits agreement, Stand Up KC wants the Royals to establish a wage floor to guarantee income for workers that reflects the cost of living of the moment. The current living wage for Jackson County is $16.68 according to the MIT living wage calculator. The current minimum wage in Missouri is $12 an hour.

Workers also want the team to agree that at least half of service and hospitality workers come from Kansas City ZIP codes with the highest rates of unemployment.

The benefits agreement also demands that the Royals agree to not engage in union-busting tactics and to allow all current stadium workers to keep their jobs and continue their collective bargaining agreement at the new stadium.

The question of a community benefits agreement was raised publicly at the second listening session, on Jan. 31 at the Kansas City Urban Youth Academy. Royals staff said the details are up in the air.

“I think it’s really important that we fully acknowledge the need and commitment around a community benefits agreement,” said Sarah Tourville, Royals senior vice president of business operations. “At the same time, I ask you to be patient with us because that community benefits agreement will be dependent upon our new home,” she added.

Workers were not satisfied with the answer.

“Regardless of where this stadium is being built, they can tell us that there will be affordable housing, that there will be a wage floor, that workers will be a part of negotiations and have a seat at the table. There are things that they can commit to even before a location is picked,” said Terrence Wise, a member of Stand Up KC.

‘We refuse to subsidize our own displacement’

While Stand Up KC organizers are focusing on worker protections, another group that primarily represents low-income Kansas Citians is staunchly opposed to the construction of a new ballpark.

Shortly before the Royals started public listening sessions, KC Tenants weighed in with a press statement.

“As landlords raise rents across the city and as our people struggle to find decent homes, the proposed downtown stadium would usher in a new wave of gentrification, like it has in so many other cities with similar recent projects,” the citywide tenants’ union said.

“The stadium downtown would threaten longtime community members, hitting our poor and working-class neighbors and the Black and brown residents of Kansas City’s east side and northeast neighborhoods the hardest. This is a bad deal for the people,” it continued.

The news release noted that taxpayers are almost certain to be asked to help pay for the new stadium and district. “The worst part? They’ll ask us to foot the bill,” it said. “We refuse to subsidize our own displacement.”

Many poor and working-class residents are already facing displacement as the rents in Kansas City continue to increase.

Stand Up KC organizers, who often are aligned with KC Tenants, say they think affordable housing should be guaranteed in the community benefits agreement. Unlike the tenants’ union, Stand Up KC thinks the development could be beneficial for workers if protections are in place.

The proposed community benefits agreement addresses affordable housing, asking the team to guarantee three new affordable housing units for every unit that gets displaced.

“We don’t outright oppose it because we want a seat at the table to negotiate these things. We want to make sure that there is affordable housing eviction prevention,” Thompson said.

What’s next?

The Royals have committed $1 billion to the construction of the entertainment district and “hundreds of millions of dollars” toward the construction of the stadium, but are looking for public funds to foot the rest of the bill.

The team said it will ask Jackson County voters to extend the 3/8-cent sales tax that was approved in 2006 for improvements on the Truman Sports Complex. Continuing the sales tax would generate $300 million to $400 million for the team over 30 years.

People familiar with development in Kansas City expect the team to also apply for developer subsidies to offset the cost of the project.

After being asked at the second listening session why he couldn’t just pay for the stadium himself, Royals owner John Sherman replied:

“We feel strongly about it being a public-private partnership to make sure that this team thrives for the next 50 years, for us to create a world-class ballpark that creates economic activity 365 days a year. We feel like we can do much more together than we can do for ourselves.”

Sherman has also said private funders and investors would be able to help offset the stadium’s cost.

As the terms and conditions of the community benefits agreement remain up in the air, Stand Up KC will continue to push for its demands.

“We know that John Sherman and the Royals will say what they have control of, but we know they have major sway. If they say they want union jobs in this district, it’ll happen. If they say they want living wages, it’ll happen,” Wise said. “These are billionaires we’re talking about.”

If workers don’t begin to see results, they will turn to other avenues to be heard, he said.

“How we got things done is rallies, protests, civil disobedience and strikes. We use every tool in our toolbox,” Wise said. “So we’ve been good stewards and listening, but when our patience runs thin and we’re not getting the results we want, we do what we do best and that’s mobilize, organize, and we take action.”

For Thompson, the path to a community benefits agreement is looking more clear.

“They seem open to the discussion, but so far, it’s just been a discussion,” he said. “It’s not anything concrete. We’re the Show-Me State, we want to see the community benefits agreement.”

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.