5:45

News Story

Missouri Attorney General candidates divided on key criminal justice reform

Do elected prosecutors in Missouri have the power to investigate past convictions and ask for a new trial when they feel a person was wrongfully convicted?

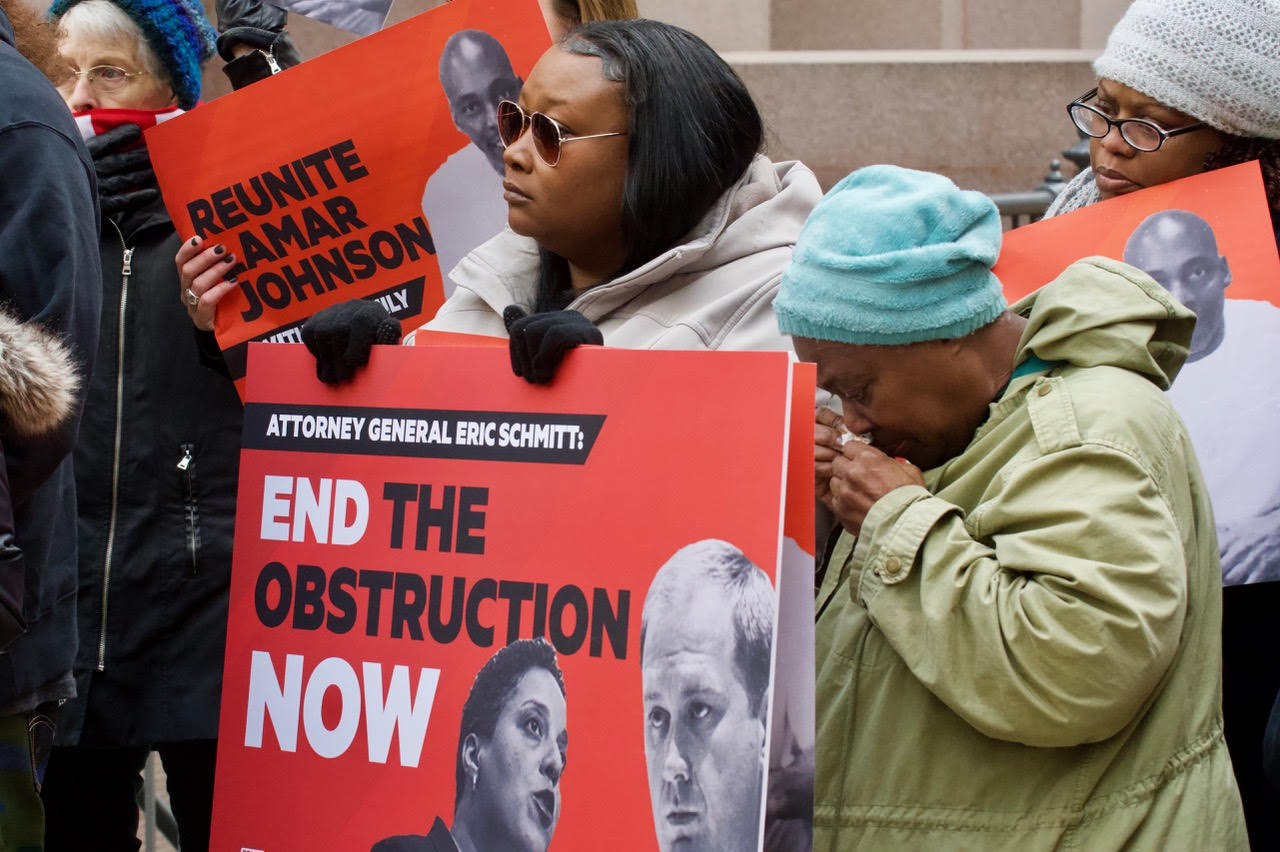

Lamar Johnson’s sister Candace Crisp and his mother Mae Johnson braved the cold to bring attention to Johnson’s case on Dec. 10, 2019, in front of the Old Post Office downtown. A group of about 25 community leaders and residents, organized by Color Of Change and Organization for Black Struggle, demonstrated outside of Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt’s office to demand that he stop trying to block a new trial for Lamar Johnson. (Photo by Wiley Price / St. Louis American)

St. Louis-native Lamar Johnson has spent 26 years in prison praying that someone would hear his case. In August 2019, that day almost came.

“I finally got taken back to St. Louis, and freedom is just right there,” Johnson said in a phone call with The Independent from Jefferson City Correctional Center. “And it was snatched away from me for something procedural that shouldn’t be more important than someone being wrongfully convicted.”

Last summer, Johnson was brought back to St. Louis for the first time in more than two decades. It was also supposed to be the first time St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner would present a case of alleged prosecutorial misconduct as part of her new conviction integrity unit.

In July 2019, Gardner asked 22nd Circuit Court Judge Elizabeth Hogan to set aside Johnson’s 1995 murder conviction, alleging that former prosecutors and police fabricated evidence to get Johnson’s conviction. Gardner filed a 67-page motion that she claims provides evidence that the homicide detective in the case made up witness testimonies for the police report that was entered into evidence. Witnesses were not aware of the changes until later.

Documents included in the motion allege that an assistant circuit attorney paid off the only eyewitness and cleared some of his outstanding tickets.

But what happened next has sparked a renewed, intense debate among attorneys and judges throughout the state — most notably between the two candidates for attorney general in the Nov. 3 election.

Do elected prosecutors in Missouri have the power to investigate past convictions and ask for a new trial when they feel a person was wrongfully convicted?

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt, who was appointed to the position in 2018 and is seeking a full term next month, says no. Prosecutors don’t have the authority to take action in cases that they feel lack integrity unless state legislators pass laws permitting this. He’s argued his position all the way to the state’s highest court through Johnson’s case.

Democrat Rich Finneran, a former federal prosecutor who is challenging Schmitt, disagrees. He says prosecutors have a duty to uphold justice, not just convictions. He is calling on Schmitt to abandon his opposition to Gardner’s motion and instead advocate to the court that Johnson be granted a new trial.

With St. Louis County and other jurisdictions looking to follow Gardner’s lead, the outcome of the case will resonate for years to come. Through 2018, conviction integrity units across the country had been responsible for producing 344 exonerations nationwide, according to an amicus brief in support of Gardner submitted to the Missouri Supreme Court signed by 45 elected prosecutors in 25 states.

A loss in this case could undermine the work of elected prosecutors nationally who are looking to increase accountability, said Miriam Krinsky, executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution.

“And it could embolden those who are trying to push back on these reform-minded leaders,” she said.

Enter Schmitt

After Gardner filed the motion in July 2019, Circuit Judge Elizabeth Hogan ordered that the attorney general’s office represent the state. Gardner, who represents the state in the City of St. Louis, disputed Hogan’s authority to bring in the Attorney General. Hogan countered that Gardner, by acting to address misconduct of a former employee, might threaten the integrity of the judicial process.

“That appointment has resulted in an unprecedented tug-of-war between two political offices who both claim to speak on behalf of the State,” according to the elected prosecutors’ amicus brief. “Johnson, in the meantime, remains stuck in the middle.”

Finneran is calling for Schmitt to take steps to secure Johnson’s release, saying the attorney general’s involvement in the case so far “is denying justice to a man who is by all accounts innocent.”

“Eric Schmitt’s responsibility is not merely to secure and protect convictions,” Finneran said, “but to do justice.”

The Attorney General’s Office declined comment because the Johnson case is still ongoing, and Schmitt’s campaign did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

However, during the Supreme Court arguments in April for Johnson’s case, Schmitt’s team said the only way for a person to seek relief is to go through the appeal process, or habeas corpus. That process can take years just to get a hearing, and historically the Attorney General’s Office opposes those appeals.

In court, the Attorney General’s Office also argued that Gardner could investigate wrongful convictions, but then she would have to turn over the evidence to the people sitting in prison and their lawyers for them to present it in court themselves.

“That’s not a very efficient mechanism,” said Missouri Supreme Court Judge Patricia Breckenridge. “We are much more likely to reach the truth of the matter if the circuit attorney, who has that information, is the party who can raise the issues before the court.”

Thirty elected prosecutors from rural Missouri counties submitted an amicus brief in support of Schmitt’s position. They stated that they, “do not desire for this court to reallocate the appellate responsibilities of the Missouri Attorney General onto their already full shoulders.”

Landmark case

This case means more than just Johnson’s freedom.

It will also define the work of the conviction integrity units not only in St. Louis but in prosecutor’s offices throughout the state that are looking to follow Gardner’s lead.

Aside from wrongful convictions, the units also independently investigate and prosecute allegations of excessive force and other wrongdoing by law enforcement. These new units are one of the strongest, most tangible results of the movement for criminal justice reform in Missouri, said some advocates and attorneys.

If the state Supreme Court sides with Schmitt, then the future work of these units will be extremely limited in scope.

The Missouri Supreme Court heard arguments in Johnson’s case on April 14.

“All we are asking for is a court to hear this evidence,” said Daniel Scott Harawa, a professor at Washington University School of Law, who argued on behalf of Gardner’s office.

There are currently about 65 conviction integrity units throughout the country, but Missouri has had the toughest time moving forward, said Lindsey Runnels, Johnson’s attorney who has worked on many wrongful conviction cases through the Midwest Innocence Project (MIP).

Runnels pointed to Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, whose unit has led to 17 exonerations since 2018.

“A defense or innocence organization could never come close to effecting the number of exonerations that a CIU can accomplish,” Runnels said. “They can do things so much faster than the lawyers on the defense side can do through traditional post-conviction challenges.”

Krasner’s office can fast track a wrongful conviction case.

“He’s got his own investigators and he’s working alongside defense lawyers,” she said. “And that’s what we would hope a conviction integrity unit would eventually be able to do here.”

Unlike Gardner, other Missouri prosecutors have been able to take action in cases they think lack integrity — including Tim Lohmar, president of the Missouri Association of Prosecuting Attorneys and the St. Charles County prosecutor.

In 2018, Lohmar moved to set aside the guilty pleas of two teenagers accused in 2015 of raping a 17-year-old woman, saying subsequent evidence cast doubt on the alleged victim’s accusation. Lohmar told Law360 that, “We felt it was our responsibility to be proactive in correcting a serious wrong.”

The attorney general did not join this case and the circuit judge did not refuse Lohmar’s motion, as the St. Louis City judge did.

“When I as a prosecutor believe that a conviction I obtained lacks integrity, I have a responsibility to make it right,” Lohmar told Law360. “It’s really that simple.”

Not willy nilly

In the states that already have a mechanism for elected prosecutors to bring forth wrongful conviction cases, they only recommend about 20 cases out of thousands of petitions, said Dana Mulhauser, chief of the Conviction and Incident Review Unit in St. Louis County.

“This is not a willy nilly undoing of the criminal justice system,” Dana Mulhauser, chief of the Conviction and Incident Review Unit in St. Louis County said. “This is fixing very specific and very egregious wrongs.

The units are a big part of addressing issues on the forefront of movement for criminal justice reform: accountability, integrity and violent crime.

“The conviction integrity unit is important in building the community’s trust with the criminal justice system,” Gardner said. “We all want the right person to be held accountable.”

Schmitt’s role in this case makes a notable difference from his predecessors, said Mike Wolff, former Missouri Supreme Court justice.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

While attorney generals in the past have perhaps disagreed with local prosecutors, Wolff said one has never overtly attacked and usurped a local prosecutor as Schmitt has done with Gardner.

“The attorney general doesn’t see himself as being on the same team as this local prosecutor,” Wolff said.

Ricky Kidd was exonerated in August 2019 after spending 23 years in prison, and he was cellmates with Johnson at one time. He knows Johnson’s case well.

Now as an advocate with the Midwest Innocence Project, Kidd explained it this way: Schmitt is like the quarterback and Gardner is the offensive coordinator — and Schmitt threw a flag on his own team.

“Something is strange about that type of leadership,” Kidd said, “when Kim couldn’t go before the court and say that, ‘We got it wrong. Here’s the remedy to make it right.’ And you come running all the way from Jefferson City, going to St. Louis City metaphorically, and saying ‘Hold on, she don’t even have the authority to do that.’ The state is challenging itself.”

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.