12:06

News Story

Jason Nelson just wants to get as close to “fairly normalized business banking” as possible.

But as the owner of Swade dispensaries and Sinse Cannabis cultivation, that’s much harder than it sounds.

He’s a customer at Triad Bank in St. Louis, one of the few banks in Missouri willing to work with cannabis businesses.

His employees have direct-deposit for payroll, 401-K contributions and full benefits packages.

But there’s a lot that’s not normal, like the company’s inability to have a business credit card.

“That’s just a non-starter for us with a cannabis business,” Nelson said.

Major credit card companies want nothing to do with a business that sells a product the federal government still considers illegal — even in states that have legalized marijuana. That means all transactions for cannabis businesses nationwide are done in cash.

Few banks nationwide serve cannabis businesses and their owners — or even their auxiliary partners – for the same reason.

“There’s this divide between the federal and the state perspective on the topic that puts banks in a kind of tricky position,” said Jackson Hataway, president of the Missouri Bankers Association.

That divide has left businesses unbanked, victims of frequent robberies and at the mercy of companies offering banking services for exorbitant fees — some that have now been deemed in violation of federal financial laws.

However, the quandary has also led to the rise of what some call a “cannabis banking ecosystem.” Central to the ecosystem are the select group of banks willing to work with these businesses and the financial technology companies that offer a variety of services to keep these businesses in federal compliance.

Missouri has benefitted from the lessons learned in banking from trailblazer states in this industry, yet it’s still a potential minefield for any business or bank.

“It’s a bit of a fraught, challenging environment,” Nelson said, “that if you don’t manage it successfully, you can just find yourself in a hard situation to imagine.”

‘Banking services’ in Missouri

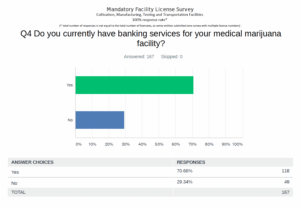

In a February 2020 survey conducted by the state, 71% of the medical-marijuana businesses said they had “banking services.”

Unfortunately in the cannabis industry, saying “banking services” is not straight forward.

It’s unclear how many banks in Missouri are serving these businesses.

A spokesperson for the Missouri Department of Finance said by law the agency can’t disclose that information.

Hataway said most banks don’t share that information with the association either, so a Google search would give the best numbers.

“It’s a small, small number,” Hataway said.

In a search, Triad comes up, along with MRV Banks in southeastern Missouri and Regent Bank in Springfield. But these banks are not at the top of the list.

It’s financial technology companies — known as fintechs — that are the biggest advertisers of cannabis banking services. These groups aren’t banks themselves, but they partner with financial institutions throughout the country and serve as the “brokers” or “agents” for those partners.

Denver-based Safe Harbor Financial, which was established in 2015, has a “large footprint” in the Missouri market, said Tyler Beuerlein, the company’s business development officer.

“We bank a number of large operators there in that market, and we’re continuing to expand those relationships,” Beuerlein said.

One of the reasons he believes his company has such a large Missouri client base is because Safe Harbor has a track record working in other states.

“There have been a number of institutions that have come into this space, and then subsequently exited quickly for a number of reasons,” he said. “The most glaring is they couldn’t meet the (federal) compliance requirements to justify keeping the accounts.”

But with all the options available, Beuerlein said he would be surprised if there were a single operator in Missouri that did not have a bank account.

“This issue has been, I believe, misrepresented far too often as being a bigger crisis than it really is,” he said.

Keri Cain, director of Regent Bank’s cannabis banking program, completely disagrees. And even more, she said it sends the message that more banks don’t need to serve this industry.

“We’re talking about a $50-billion industry that is largely unbanked,” she said. “Nationwide, there’s probably less than 700 banks that bank cannabis. That’s ridiculous. We have got to get more banks in the game.”

Heartbeat of the problem

The reason more banks don’t want to get in the ring — particularly those in rural areas — is capacity, Cain said.

Cain has a team of eight bankers that solely focus on cannabis accounts, which come from about 21 different states. The ratio of bankers to these accounts is much lower than standard business banking, she said.

“We’re required to report out every 90 days,” she said. “We want to make sure that we’re doing what’s required of us.”

Like fintechs, they also use apps and technology to support the compliance side and ease of banking operations.

Regent Bank is based in Oklahoma and has a location in Springfield.Although marijuana is illegal at the federal level, banks can provide services to the marijuana industry if they follow the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) guidelines.

But the amount of policy-writing, legal counsel and inspections required can be “very cumbersome,” said Jim Regna, CEO and founder of Triad Bank.

“Most banks have decided that, for now, it’s not right for them,” he said.

The “heartbeat of the problem” goes far beyond the cannabis industry, Hataway said.

For many banks, some of their biggest customers are local-business owners. When those owners decided to open cannabis businesses, their banks were no longer able to keep them as clients, Hataway said.

FinCEN has strict regulations on providing services to owners of cannabis businesses, as well as any business that receives 50% or more from supporting the cannabis industry.

Hataway uses the example of real-estate owners who want to lease space to cannabis businesses but can’t because it could jeopardize their relationship with their bank.

“You can just see how the ripple effect is so strange,” Hataway said. “It makes banks very hesitant. And they have to really peel back the layers of onion on customers and businesses that otherwise you wouldn’t even think twice about.”

The association is advocating for the federal Safe Banking Act, which is proposed legislation aiming to allow banks to do business within states that have legalized marijuana. It’s cleared the House several times, but has not yet passed.

“So we remain in the current quagmire we’re stuck in,” he said, “where you have a lot of states like Missouri that have upward pressure from businesses to have a secure and safe banking environment. Because if they’re all cash, they’re very risky.”

Understanding the ecosystem

D.C.-based attorney Josh Radbod has been working with fintechs, cannabis-related businesses and financial institutions for the past six years.

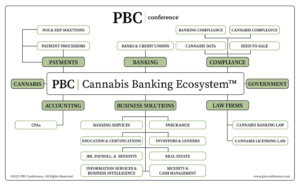

In 2018, he and a friend hosted the first annual PBC Conference, which is geared towards players in the payments, banking and compliance side of the cannabis industry.

Last year, the organizers put out the “Cannabis Banking Ecosystem” report, which describes the role of each player — fintechs, lawyers, accountants, government agencies, and banks. They also published directories of services nationwide at every level.

There are fintechs that specialize in supporting banks and businesses in compliance. Others focus on acting as “licensed money transmitters.

Every fintech has a bank partner in some way or another, so they are a big piece of the web — as are government agencies.

“Interestingly, there were no banks in Missouri that either bank cannabis or we’re willing to publicly say that they bank cannabis,” he said.

However, Regent Bank was listed under a “nationwide” heading. Radbod estimates there’s between 200 to 300 banks and credit unions nationally that are currently setting up depository accounts for cannabis operators.

His estimates were less than half of Cain’s, but Radbod said he doesn’t believe there is a crisis.

“I doubt any of the industry is unbanked anymore,” he said. “Because if someone’s unbanked and they just go look at this directory and make five phone calls, they’ll get a bank account.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Jackson Hataway.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.