9:00

News Story

Grain Belt transmission line forges ahead amid landowner, lawmaker pushback

Boosters say a transmission line like Grain Belt could have helped prevent the rolling blackouts seen this winter.

On the heels of a historic cold snap that left thousands across the Midwest without power, Kansas and Missouri residents could soon reap the benefits of a massive high-powered transmission line delivering renewable energy.

Grain Belt Express, a project a decade in the making, is starting to acquire land along its route spanning across nearly the width of both states. But even so, landowners, local officials and some Missouri lawmakers are still raising red flags, arguing the project will be destructive to rural communities.

The proposed Grain Belt Express, being developed by Chicago-based Invenergy, would run from near Dodge City, Kansas, to Indiana, moving 4,000 megawatts of power per year.

In Missouri, 39 municipal utility providers have signed up and expect to save $12.8 million per year. Grain Belt promises thousands of jobs — both to construct and operate the line. The company could revise its plans to drop off more power in Kansas and Missouri, saving up to $7 billion a year over 20 years for up to $2.4 million residents.

And had Grain Belt been in operation this winter, Nichole Luckey, vice president of regulatory affairs for Invenergy, said the ability to transmit lots of power quickly could have helped prevent rolling blackouts seen in Kansas and Missouri. The line, she said, would serve as a “reliability backbone” for the Midwest.

“The outages in February are just more evidence that this line is really critical,” she said.

Luckey said the company believed the project offered landowners the most competitive compensation in the state’s history and noted the state government found it was in the public interest to build the line.

But even as Invenergy begins negotiations with farmers to compensate them for running the line across their land, it’s still facing resistance from both landowners and Missouri lawmakers. The Missouri House once again voted overwhelmingly in favor of legislation designed to pump the brakes on Grain Belt’s plans.

The legislation would require projects — including Grain Belt — that use eminent domain to acquire land to show support from the county commission in any county where the project is expected to build.

Grain Belt already has approval from the Missouri Public Service Commission, granting it status as a public utility, but the legislation would make that retroactively dependent on its ability to persuade county commissioners in the eight counties the transmission line will cross, many of whom are vocally opposed to to the project.

John Truesdell, presiding commissioner in Randolph County, said he has advocated for bills to stop what he calls “eminent domain for private gain.”

Grain Belt, he said, is “nothing more than a big corporation trying to overrun little people, take their homes, take their land and pocket the money in their pockets at those other people’s expense.”

Meanwhile, in Kansas, the project has two more years to make progress assembling the land for the project before it loses its right to build there.

Missouri Rep. Mike Haffner, R-Pleasant Hill, is sponsoring the Grain Belt legislation. He argued to a House committee the project should not be allowed to use eminent domain.

“(It’s) supposed to be used by the government as a means of serving the public, and I think in this case it doesn’t serve the public,” he told a House committee hearing the legislation in January.

Luckey said the bill would, without a doubt, kill the project.

“This project has been through 10 years of hearings, public meetings, and to retroactively require these approvals at the local level turns the regulatory paradigm on its head,” she said.

A similar bill cleared the House last year but didn’t make it through the Missouri Senate. The House did, however, slip another piece of legislation meant to stall the Grain Belt project past senators, but the Senate later revoked it in a rare procedural move that a House leader questioned.

Property rights

The fight over Grain Belt in Missouri boils down to property rights.

The project has the right of eminent domain in both Kansas and Missouri, meaning that Grain Belt can acquire easements on private land to build the line — even in cases where the landowners don’t want to negotiate.

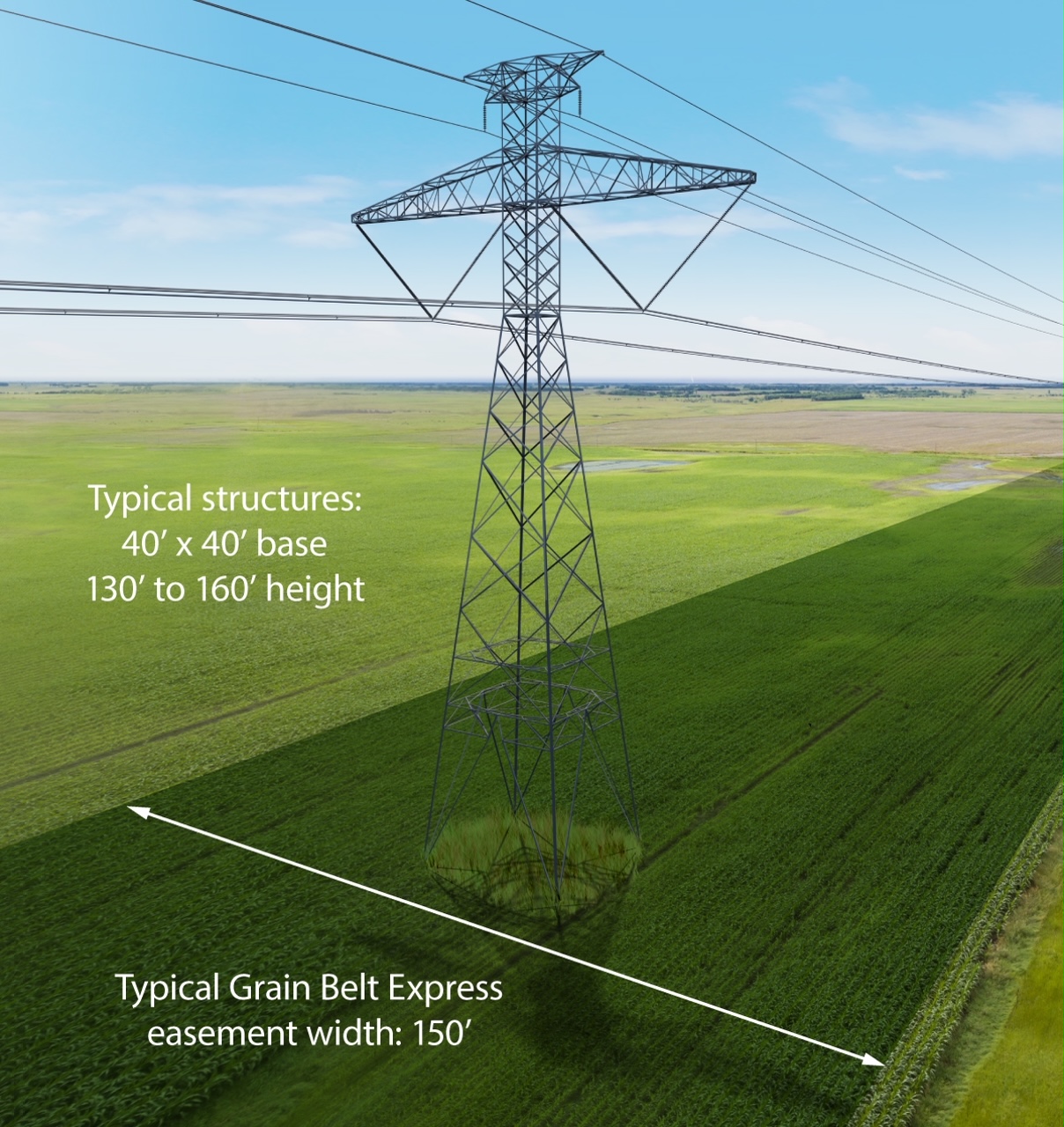

Landowners will be compensated for their land, and company executives note they would still be able to hunt, farm or graze livestock on the area where Grain Belt operates. The company would not acquire the land itself, but the right to use it.

Beyond that, eminent domain, the company says, will only be used as a last resort. In recent months, the company has started sending offers to the landowners along the route.

So far, the company says it has acquired rights to about 40% of the necessary land in Kansas and Missouri. It says it’s offering landowners 110% of market value for the easements, plus additional payments for structures on their land and to offset any impact to their crops.

Utilities never want to use eminent domain, said Peggy Whipple, an attorney representing Grain Belt. But without it, one landowner who didn’t want to grant the line an easement could sink the project.

“If you take away a public utility’s right to eventually, if necessary, use eminent domain, you might as well just accept that a big project like this isn’t going to happen,” Whipple said, also adding that the legislation unconstitutionally targets a single project and could open the state to a lawsuit.

Critics argue Grain Belt is being built by a private company seeking to make a profit, meaning it is being allowed to take other private property for its own gain, not the public’s.

“I hate to say this and I doubt I’d ever thought myself saying this, but right now we’re using government-sanctioned confiscation of private property,” Wiley Hibbard, presiding commissioner in Ralls County, said in a House committee meeting early this year.

Landowner after landowner, some with farms passed between six or seven generations, turned out to a Missouri House committee meeting in January to urge lawmakers to support Haffner’s legislation.

Donna Inglis, however, said her family got a fair deal from Grain Belt to build across their farm in Randolph County. She urged fellow landowners who decried the proposal to “think about our state and the future of our state.”

“If no one were in favor of progress…we would still be living by kerosene lamp and going to the out house,” Inglis said.

Though the Kansas portion of the line is nearly twice as long, lawmakers aren’t putting up the same fight.

But there are still hurdles, said Dave Nickel, executive director of the Citizens Utility Ratepayer Board, which represents ratepayers in Kansas.

When the Kansas Corporation Commission authorized Grain Belt’s construction through the state, it said construction on the transmission line could not begin unless Missouri, Illinois and Indiana had approved the plan in those states.

Initially, the KCC set a sunset on Grain Belt’s permission to build in Kansas so landowners wouldn’t have the possibility of a transmission line hanging over their heads for years. But in 2019, the company requested an extension because of delays in Missouri and Illinois.

Now, the company has until Dec. 2, 2024, to show Kansas regulators it has either acquired — or started negotiations or court proceedings to acquire — easements on the majority of the land needed to build the transmission line, something Luckey said should be no problem.

“It’s going to be a difficult chore, but I’m sure it’s an obtainable chore,” Nickel said.

Prospects for passage

In Missouri, House members have led the charge against Grain Belt. In 2020, the same bill was the first to pass the body.

It died in the Senate. The same is likely to happen this year. The House passed the bill in February, but now it’s languishing in a Senate committee where senators have yet to hear testimony on it with less than a month before the legislature adjourns for the year.

In a separate attempt to slow down the project last year, the House tacked an amendment onto another bill that would have allowed county historical societies or county commissions to deem some farm property as historic, driving up the cost to acquire it through eminent domain.

Senators gave the bill final approval without realizing what the amendment would actually do or how it might impact Grain Belt. When they figured it out a day later, they voted unanimously to rescind their approval.

But then-House Speaker Elijah Haahr, who had made the eminent domain legislation his top priority, argued Senate rules didn’t allow for approval to be rescinded.

“The extreme and unprecedented actions by the Senate after a bill’s final passage are alarming,” Haahr wrote in a letter published in the House Journal May 28, 2020. “It appears that such an action has not been taken by either chamber in 100 general assemblies and for good reason.”

Haahr argued the Senate’s move was illegal, meaning the bill passed. In Missouri, if a governor doesn’t sign or veto a bill approved by lawmakers, it becomes law. Parson’s office didn’t respond to inquiries about the legislation.

But Chuck Hatfield, an attorney who frequently handles high-profile cases involving legislation and initiative petitions in Missouri, doesn’t believe the bill actually became law.

Several county commissioners told The Independent they weren’t aware of any efforts to designate historic farm property on the Grain Belt route.

If someone wanted to make the case it should be in effect, Hatfield joked, they should hire him to take it on.

Luckey said the company is not aware of anyone attempting to invoke the legislation — “primarily because it didn’t pass.” But she noted Missouri law already requires higher compensation for “heritage value” for farms that have been in the same family for more than 50 years.

If a landowner can document they have a heritage farm, Luckey said Grain Belt would pay them a higher value. If possible, Luckey said the company would like to acquire all of the land voluntarily and avoid eminent domain altogether.

“We want to be fair.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.